Safety is a big consideration each day. Not only in the equipment we use, but also in the route we choose. Below are some of the key safety items of this trip:

Daily Coastguard Passage Plans

Each day when we get in the water, Joe would use the VHF radio to call through to the coastguard with a passage plan. The main information he’d provide was:

- The name of our support vessel – Mentor

- The fact Mentor will be assisting two kitesurfers in the water

- The colour of our kites and boards

- Our current/starting location

- Our intended destination

- Our estimated time of arrival.

At the end of the day, Joe would then call back indicating where we’d moored for the night, and the fact we’d arrived. This is especially important as we didn’t always make it to where we initially intended. If there was a significant change in plan, he would call back intra-day. For example when we went from Newhaven to Yarmouth, we were initially aiming for Chichester. When it became apparent we could go further, we updated the coastguard of our new intentions. Similarly off the coast of Scarborough, crew on a windfarm had reported kiters close to the equipement, and they called Joe asking if this was us, or someone else, possibly in trouble.

Overview E-mail to the Coastguard

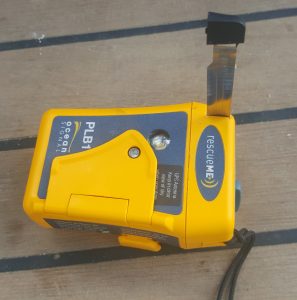

There are 18 coastguard areas in the UK. We didn’t visit all of them, e.g. Area 1 is the Shetlands, which were too far off the coast of Scotland for this trip. As we entered into each new area, Joe called through with an overview of what we were attempting, and often they requested an e-mail with more specifics of the trip. This e-mail included information such as a picture of Mentor; emergency contact names/numbers; VHF call sign; and serial numbers of our EPIRBS/PLBs.

Why call into the coastguard?

This was two fold. First, if something went wrong with Mentor and as kiters we weren’t able to get back to it, then they know an approximate area in which to look for us. This is good practice for all shipping activity. Second, we were kiting further offshore than most people are used to seeing. If anyone called through thinking we were in distress, then they had our location, so could contact us to see if the call related to our activities or other beach goers. This potentially avoided any unnecessary call out.

Personal Safety Equipment

As kiters we had our own safety equipment on our person. We had the regular safety features most modern kites have, plus some additional items due to the distances we were covering.

Regular Kite Safety Features

De-Power Strap

All modern kites have a depower strap. This is attached to the middle lines and can usually be used to trim the kite. I’ll use this on a regular day if the wind picks up or even if I change my angle of sail. (You need less power when you go downwind)

Chicken-loop

There’s a quick-release on the chicken-loop. This is the section of bar that loops around the hook on your harness and takes the weight of your kite. By releasing this, the kite will depower down onto a single line. The kite is still attached to you by your safety, but there is usually very little power in it at this stage.

Safety Leash

Your safety. This is connected to a single middle line, and runs back to your harness. When the chicken loop is pulled the bar will run up the lines, causing all but one to go slack. There are a whole class of free-style moves called “Unhooked” moves, where the rider will disconnect their chicken-loop from their harness to make a more elongated shape. If at this point they accidentally let go of the bar, the kite will de-power but they will still be connected to the kite by their safety. To retrieve your kite you can walk back along the line your safety is connected to back to the kite, reconnect your chicken-loop and continue kiting.

If you want to detach from your kite completely, the safety has a quick release. This detaches the rider from the kite completely and depending on how fast your rescue cover is, can result in the loss of your kite off downwind, never to be seen again.

Items Specific for Travelling

Buoyancy Aid

If the wind dropped, we may remain sitting in the water for a while waiting for it to come back. This helped to keep us floating, they also had lots of pockets!

Even if we’re not travelling, when using a foil board, it is recommended to wear either a buoyancy aid or an impact vest. This is in case you fall in such a way that the foil rebounds and hits you. Helmets are also recommended for this exact reason.

Water Store

There is a sleeve on the back of our buoyancy aids that held a water pack. Although not directly a piece of safety, it was important we didn’t get dehydrated on a long hot day, as this could impact our judgement/ability to kite

Personal Locator Beacon (PLB)

We each carried one of these in our buoyancy aids. If we somehow get detached from each other or from Mentor and were unable to safely make it back to a beach, we could activate these. They emit a distress signal that can be picked up by the coastguard. Each device has it’s own identification code, which is registered so if activated they know who they are looking for. We sent details of ours to each coastguard as we enter their area.

Helmets with Bluetooth Communication Devices

Definitely when riding on a foil board, I’d recommend wearing a helmet. But similar to snow sports its becoming more common to see riders wearing these when kiting. On our helmets we mounted Bluetooth headsets. This allowed Stew, Islay and Joe to communicate with one-another throughout the day. This was great for discussing everything from a dropping or strengthening wind to which direction we need to head or what to aim for. However, because these are always on (as opposed to the VHF radios which are push to talk), the most useful feature of these was to detect when someone had fallen. Whenever there is a crash you hear the swoosh of water through the headset, so you know to look around at the other rider in case they’ve lost their board, crashed their kite or you need to slow down to wait for them. They do have their drawbacks though: you couldhear when Joe was crunching an apple or eating crisps. Such a tempting sound if you’ve been going all day on just a bowl of porridge.

Definitely when riding on a foil board, I’d recommend wearing a helmet. But similar to snow sports its becoming more common to see riders wearing these when kiting. On our helmets we mounted Bluetooth headsets. This allowed Stew, Islay and Joe to communicate with one-another throughout the day. This was great for discussing everything from a dropping or strengthening wind to which direction we need to head or what to aim for. However, because these are always on (as opposed to the VHF radios which are push to talk), the most useful feature of these was to detect when someone had fallen. Whenever there is a crash you hear the swoosh of water through the headset, so you know to look around at the other rider in case they’ve lost their board, crashed their kite or you need to slow down to wait for them. They do have their drawbacks though: you couldhear when Joe was crunching an apple or eating crisps. Such a tempting sound if you’ve been going all day on just a bowl of porridge.

VHF Radios

These were mainly used as a backup, in case the Bluetooth headsets stopped working. They are “push-to-talk”, so unlike the headsets, you needed to actively engage them. To make this easier we attached a speaker to the shoulder of our buoyancy aids. They would also allow us to contact the coastguard/other vessels if somehow either of us got detached from Mentor. (Which thankfully never happened)

The way our Bluetooth headsets work is there is one master, so if you get disconnected from the master the others cannot talk to each other. Having the VHF allowed us to still communicate in these scenarios.

Keeping Close

The most important aspect, is we try to keep close to each other. If all communication fails, we can still use hand signals or kite really close.