We’ve been to so many amazing places it would be hard to choose. I think the best bit about the trip is everywhere’s been different. However whenever pushed, the answer always seems to revolve around food. Not sure why that is? There’s been so many breathtaking landscapes, but we all look to our stomachs. At least on the food front we’re all in agreement – the strawberry ice cream at Kilmore Quay, Ireland. We were stuck here for 6 days, and only discovered the ice cream on day 4. Mistake! Kilmore Quay is in county Wexford, famous for it’s strawberries. Sadly the local corner store never had any in stock, as most people buy directly from the farmers (who were too far away to visit on foot). But the ice cream, was like eating real, fresh, sweet, juicy strawberries. Amazing! Each day has been unique. Our schedule is mainly driven by the wind, and sometimes the tide. Some parts of the country, such as the Pentland Firth (at the north-eastern tip of Scotland) the tide or current can flow at up to 15knots. At others, it’s under 1knot. If you have the tide against you this can really affect your speed, sometimes meaning its not worthwhile trying as it drags you so quickly the other way. However, to give you a rough idea I’ve set out an example below: 07:00 Alarm 07:30 Departure 08:30 Motor to our starting point 09:00 Launch the Dinghy 09:15 Rig up and launch 09:30 Mentor sets off 10:00 Kite 16:00 Pack up 17:00 Anchor 19:00 Dinner 20:00 Gin Rummy 22:00 Bed Stew and Islay have two boards each, a twin-tip and a foil board. Most people when they learn to kite will learn on a twin-tip, but over the last few years foil-boards have really started taking off. This trend will likely continue growing with the news earlier this May of kite-racing being added to the 2024 Olympics. On this trip, when we’re travelling, there are two main factors which determine our board choice: Similar to sailing boats, we cannot travel directly into the wind. Therefore we will travel at an angle each side of the wind, tacking between the two to reach the desired upwind direction. Foils because they travel faster create apparent wind and can go at a tighter angle to the wind than a twin-tip. A twin-tip because of the additional friction in the water can only make approximately 80 degrees to the wind, hence creating a lot longer/slower progress upwind. (It is also more effort for the rider). Hence most upwind days on this trip we’ll usually be on our foil boards. Once the foil board breaches the surface, it requires very little power from the kite to continue propelling you forward. Therefore if the wind is marginal, we will usually be using our foils. Conversely if the wind is on the upper end of the spectrum, you can handle more power on the twin-tip. This is because you can dig the rail/edge of the board into the water counteracting the pull and power in the kite. Depending on how strong the wind is, you may want to use a different size kite. Kites are measured in square meters, however when you see this written or verbalised, the “square” is oftem omitted. For this trip we have PeterLynn kites ranging from 5m2 to 15m2. The bigger the kite, the more powerful it is, and usually the less wind you need to fly it. Below are some factors to consider when choosing which kite size to use: As hinted above, the strength of the wind is the biggest factor in choosing which kite to use. Too big a kite in too strong a wind will mean the rider is over powered, possibly resulting in the kite pulling them over forwards and crashing more. Too small a kite, and the rider may not be able to get onto the board to ride. The heavier you are, the more power or energy you need from the kite to lift yourself up off the water. To achieve this you move the kite in a large “power stroke”. The process of standing up is usually when you need the most energy from the kite. Stew and Islay are approximately 20kg apart, so on twin tips they will usually be on kites 2m2 apart. (Does mean neither of us can gain/loose weight without the other doing the same). If it’s flat calm on a twin-tip board you can hold a lot more power than in rough seas, as you can really lean back, using your body as a lever to counteract the power (known as holding your edge). In rough seas this is harder to do, as if you lean too far back a wave can come and dunk you in. Similarly, too depowered in waves means you may start sinking as try to ride up and over a wave crest. If riding a twin-tip, you generally need slightly more power than on a foil. This is because once a foil is out of the water there is very little friction, so less power is needed. In our blogs, we’ll sometimes mention changing board types intra-day. This is because it is faster than changing kite sizes. If we are slightly overpowered on our foil-boards, we can change to the twin-tips and the extra friction from the boards being in constant contact with the water means we can handle more power. (We’re also more experienced on our twin-tips). Which kite you use will also depend on what you have. Most riders will have a quiver of two kites. A common quiver for the south coast of England would be a 12m2 and a 9m2. These sizes are far enough apart that the wind range of the two kites won’t overlap too much while not having too big a gap between them. Depending on where the rider’s local spots are they may want a different set. For example, in Nassau (Bahamas) the wind is usually lighter, so the same person may instead choose to have larger kites in their set, e.g. possibly a 15m2 and a 12m2 Safety is a big consideration each day. Not only in the equipment we use, but also in the route we choose. Below are some of the key safety items of this trip: Each day when we get in the water, Joe would use the VHF radio to call through to the coastguard with a passage plan. The main information he’d provide was: At the end of the day, Joe would then call back indicating where we’d moored for the night, and the fact we’d arrived. This is especially important as we didn’t always make it to where we initially intended. If there was a significant change in plan, he would call back intra-day. For example when we went from Newhaven to Yarmouth, we were initially aiming for Chichester. When it became apparent we could go further, we updated the coastguard of our new intentions. Similarly off the coast of Scarborough, crew on a windfarm had reported kiters close to the equipement, and they called Joe asking if this was us, or someone else, possibly in trouble. There are 18 coastguard areas in the UK. We didn’t visit all of them, e.g. Area 1 is the Shetlands, which were too far off the coast of Scotland for this trip. As we entered into each new area, Joe called through with an overview of what we were attempting, and often they requested an e-mail with more specifics of the trip. This e-mail included information such as a picture of Mentor; emergency contact names/numbers; VHF call sign; and serial numbers of our EPIRBS/PLBs. This was two fold. First, if something went wrong with Mentor and as kiters we weren’t able to get back to it, then they know an approximate area in which to look for us. This is good practice for all shipping activity. Second, we were kiting further offshore than most people are used to seeing. If anyone called through thinking we were in distress, then they had our location, so could contact us to see if the call related to our activities or other beach goers. This potentially avoided any unnecessary call out. As kiters we had our own safety equipment on our person. We had the regular safety features most modern kites have, plus some additional items due to the distances we were covering. All modern kites have a depower strap. This is attached to the middle lines and can usually be used to trim the kite. I’ll use this on a regular day if the wind picks up or even if I change my angle of sail. (You need less power when you go downwind) There’s a quick-release on the chicken-loop. This is the section of bar that loops around the hook on your harness and takes the weight of your kite. By releasing this, the kite will depower down onto a single line. The kite is still attached to you by your safety, but there is usually very little power in it at this stage. Your safety. This is connected to a single middle line, and runs back to your harness. When the chicken loop is pulled the bar will run up the lines, causing all but one to go slack. There are a whole class of free-style moves called “Unhooked” moves, where the rider will disconnect their chicken-loop from their harness to make a more elongated shape. If at this point they accidentally let go of the bar, the kite will de-power but they will still be connected to the kite by their safety. To retrieve your kite you can walk back along the line your safety is connected to back to the kite, reconnect your chicken-loop and continue kiting. If you want to detach from your kite completely, the safety has a quick release. This detaches the rider from the kite completely and depending on how fast your rescue cover is, can result in the loss of your kite off downwind, never to be seen again. If the wind dropped, we may remain sitting in the water for a while waiting for it to come back. This helped to keep us floating, they also had lots of pockets! Even if we’re not travelling, when using a foil board, it is recommended to wear either a buoyancy aid or an impact vest. This is in case you fall in such a way that the foil rebounds and hits you. Helmets are also recommended for this exact reason. There is a sleeve on the back of our buoyancy aids that held a water pack. Although not directly a piece of safety, it was important we didn’t get dehydrated on a long hot day, as this could impact our judgement/ability to kite We each carried one of these in our buoyancy aids. If we somehow get detached from each other or from Mentor and were unable to safely make it back to a beach, we could activate these. They emit a distress signal that can be picked up by the coastguard. Each device has it’s own identification code, which is registered so if activated they know who they are looking for. We sent details of ours to each coastguard as we enter their area. These were mainly used as a backup, in case the Bluetooth headsets stopped working. They are “push-to-talk”, so unlike the headsets, you needed to actively engage them. To make this easier we attached a speaker to the shoulder of our buoyancy aids. They would also allow us to contact the coastguard/other vessels if somehow either of us got detached from Mentor. (Which thankfully never happened) The way our Bluetooth headsets work is there is one master, so if you get disconnected from the master the others cannot talk to each other. Having the VHF allowed us to still communicate in these scenarios. The most important aspect, is we try to keep close to each other. If all communication fails, we can still use hand signals or kite really close. We’re estimating we’ll travel about 3,000 miles around the coast of Great Britain. But the official coastline is measured as 11,072.76 miles. Why the difference? We’re not following each and every bay, cove and river mouth. A good example of this would be when we crossed the Thames estuary. We crossed from Harwich, to North Foreland. However the Ordnance Survey measures the coastline at mean high water. The Thames is tidal up until Teddington, which is all the way up, past the city of London. The river narrows so much up there we wouldn’t be able to kite. Not only this, but the river traffic and wind shadows from all the tall buildings and bridges would make it impossible to kite. An example of how much this would have cut off is given below. The blue line was Mentor’s actual track crossing the estuary from Harwich to Ramsgate – 54 miles. The green line I’ve followed the southern coastline as closely as possible, measuring 108 miles. And slightly less accurately the north coast in orange as 100 miles. The Thames isn’t the only place we’ll be cutting out sections of coast like this. On our second day we crossed The Wash; coming up in June we’ll cross the Bristol Channel; and in Scotland there are no end to the number of lochs we won’t be able to explore. The second reason why our estimate is not exact is due to the Coastline Paradox. This has to do with what your minimal measure of accuracy is. Coastlines can be broken down into smaller and smaller pieces, it’s impractical to measure every pebble on each beach, but these smaller pieces still make up the coastline, and affect the distance. The coastline paradox says that there is always a smaller measurement that could be measured, and it is therefore impossible to calculate an exact number. To find out more on this see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Coastline_paradox When we’re kiting, we can’t always travel in a straight line. Similar to most sailing vessels, we can’t head straight into the wind as there is no pressure in the kite. We cannot travel directly downwind for exactly the same reason. Therefore the “Distance Kited” is almost always longer than the “Distance Travelled”, which is measured by a straight line along the coast. A good example of this was on May 6th: The blue line is Mentor, the white Islay and the red Stew. The wind was coming from the East. Stew and Islay on their kites had to “beat” upwind, ie tack back and forth in order to get upwind (the zig-zags you see). Where as Mentor could head in a straight line. On May 6th we kited 52 nautical miles, but only travelled across the ground 22 nautical miles. Where’s been your favourite place?

What’s a typical day?

Joe is an early riser, so porridge is usually ready waiting for us just as the alarm goes. Talk about being spoilt!

Once we’ve all eaten breakfast, and used the onshore facilities we’ll set off. (We don’t have a holding tank, so if we’re in a Marina we have to go ashore to use their facilities. This is a general courtesy, as you can imagine the quality of the water if all the boats flushed overboard).

If the wind allows we’ll try to stop as close to where we’re going to stop for the night as possible. But sometimes this doesn’t always happen. We’ve had to motor up to three hours to return to our finish point so we can start again. (The worst being Ramsgate and Kilmore Quay (Ireland)).

At night we’ll hoist the dinghy using the davits onto the back of the boat. This stops it from banging against the hull waking us in the middle of the night, but also means there’s one less thing to worry about when we’re anchoring or coming into the marina.

Towards the start of the trip it was taking us about an hour to get ready in the morning. But by the end we’ve now got this down to under 15minutes. Stew, Islay and Jeremy will all get into the dinghy with the chosen kites for the day, pump and two boards. We’ll then launch first Islay, then Stew from the dingy.

Depending on the wind direction, we’ll either hang around nearby Mentor while Jeremy motors back and connects the tow line. Or, if we know we’re going to be slower, we’ll set off and Joe will catch up.

That’s why we’re here! We’ll kite until either the wind dies, the tide changes, we’ve reached our intended destination or the light fades. Occasionally we’ll need to change kites due to a changing in wind strength, in which case Jeremy will be deployed with the new gear and we’ll launch from the dinghy (without going back to Mentor). If we’re lucky he’ll even bring us a snack.

We pack up one at a time. Rolling our lines while we’re in the water. Jeremy will then pickup the kite and deflate it in the dinghy. To avoid getting our lines twisted we have to be careful when putting away the kites. If we do a speedy pack down, and just bunch the kite in the boat, it can take up to an hour later on in the evening to sort it out again.

We don’t always stop kiting where there’s a convenient place to anchor or moor for the night, so we sometimes have a ways to motor before we can stop. This gives us a chance to get dinner ready.

Stew is usually chef, Jeremy DJ and Islay/Joe the washers up. After a long day’s kiting we all have very healthy appetites. It’s going to be hard getting used to normal portion sizes again when we’re done!

Throughout the trip there’s been a healthy competition at night, with the winner often rotating each day.

On occasion we’ll organise anchor watch, where one of us will get up every hour to make sure our anchor hasn’t dragged, and we’re still in a safe location. But most nights as soon as my head hits the pillow, I’m fast asleep. When do you use which board?

Direction of Travel

Downwind is similar, you cannot head in the same direction as the wind is blowing. Both Stew and Islay are relatively new to the foil boards, our angle is wider than most professionals, so actually we make better downwind track on our twin-tips.Wind Strength

On a foil you can become overpowered quite easily. If you are feeling overpowered, you can either head further into the wind, if you’re going in an upwind course, or head further away from the wind if heading downwind. This will help release the power in the kite and slow you down. If however you’re going on a beam reach, i.e. at 90 degrees to the wind, so neither up- or downwind then there is no way of releasing the power. This can make it a difficult direction on the foil boards if you’re not on the perfect size kite. How do you choose what size kite to use?

Wind Speed

Rider’s Weight

Sea State

Board choice

Quiver Size

What safety precautions do you take?

Daily Coastguard Passage Plans

Overview E-mail to the Coastguard

Why call into the coastguard?

Personal Safety Equipment

Regular Kite Safety Features

De-Power Strap

Chicken-loop

Safety Leash

Items Specific for Travelling

Buoyancy Aid

Water Store

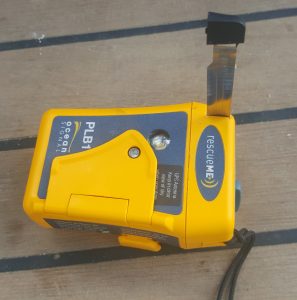

Personal Locator Beacon (PLB)

Helmets with Bluetooth Communication Devices

Definitely when riding on a foil board, I’d recommend wearing a helmet. But similar to snow sports its becoming more common to see riders wearing these when kiting. On our helmets we mounted Bluetooth headsets. This allowed Stew, Islay and Joe to communicate with one-another throughout the day. This was great for discussing everything from a dropping or strengthening wind to which direction we need to head or what to aim for. However, because these are always on (as opposed to the VHF radios which are push to talk), the most useful feature of these was to detect when someone had fallen. Whenever there is a crash you hear the swoosh of water through the headset, so you know to look around at the other rider in case they’ve lost their board, crashed their kite or you need to slow down to wait for them. They do have their drawbacks though: you couldhear when Joe was crunching an apple or eating crisps. Such a tempting sound if you’ve been going all day on just a bowl of porridge.

Definitely when riding on a foil board, I’d recommend wearing a helmet. But similar to snow sports its becoming more common to see riders wearing these when kiting. On our helmets we mounted Bluetooth headsets. This allowed Stew, Islay and Joe to communicate with one-another throughout the day. This was great for discussing everything from a dropping or strengthening wind to which direction we need to head or what to aim for. However, because these are always on (as opposed to the VHF radios which are push to talk), the most useful feature of these was to detect when someone had fallen. Whenever there is a crash you hear the swoosh of water through the headset, so you know to look around at the other rider in case they’ve lost their board, crashed their kite or you need to slow down to wait for them. They do have their drawbacks though: you couldhear when Joe was crunching an apple or eating crisps. Such a tempting sound if you’ve been going all day on just a bowl of porridge.VHF Radios

Keeping Close

Isn’t the coastline of Great Britain more than 3,000 miles?

Shortest distance between two points is a straight line

Coastline Paradox

Whats the difference between “distance travelled” and “distance kited”?